A Poisoned Dairy Farm in Maine

--

Fred Stone and his family has operated the Stoneridge Dairy Farm in Arundel, Maine since just after the turn of the 20th century in 1905, but today as a result of high levels of PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), often referred to as 'forever chemicals,' synthetic chemicals used widely in many consumer goods, his farm is failing.

Since 1914, dairy cows on Stone’s farm provided milk to Maine milk co-ops, and they were eventually bought by Oakhurst Dairy, one of the country's largest distributors of milk products. But a phone call on November 3, 2016 changed that.

Stone recalls the conversation. “‘We can't take your milk anymore Fred,' is what [Oakhurst] told me. ‘The levels are too high’, and that is when our nightmare began.”

Oakhurst officials were referring to the levels of PFAS chemicals, which have been found to be hazardous to human health per the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) Lifetime Public Health Advisory of 2016 and ongoing studies, in the milk that Stone was providing from his dairy cows. Oakhurst's testing showed that the milk from Stone's cows had 1410 parts per trillion (ppt) of PFAS, significantly higher than the accepted level of 210 (ppt) at that time. Stone had never heard of PFAS before that moment. But as a result of the high PFAS levels, his dairy farm business was decimated.

PFAS chemicals are found in a wide variety of products, from fire prevention foam to waterproof fabrics. But when found in milk, on a dairy farm in rural Maine, they can be dangerous. Just this month, in April 2024, the EPA announced that drinking water providers must reduce the levels of PFAS in water to 4 ppt, significantly lower than that of the previous acceptable level of 70 ppt. There currently isn't an action level for PFAS from the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) for drinking milk.

'I couldn't have children drinking that milk, I had to find a way to make things right and still be a dairy farm.'

The origins of Stone’s experience with PFAS can be traced back to a program started in the 1970's when the state of Maine offered farmers wastewater sludge, a solid byproduct of wastewater treatment, for use on farms in existing slurry pits, or waste storage ponds, where manure is stored and eventually spread on the fields for fertilization. This offer of free fertilization material appealed to farmers around the state, and according to the state, the waste was safe for this use. Not only did Stone take advantage of this material, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection hired Stone to deliver and spread this material to other farmers in his area from 1983 to 2004. Years later though, the waste sludge has been determined to be the source of the PFAS, despite the initial assurances that it was safe.

After the call from Oakhurst in 2016, Stone slaughtered 125 of his cows with the hope that getting a new herd would help solve the problem. It was a tough choice to make - to a dairy farmer, cows are an extension of the family. But he soon learned how contaminated his farm was - within a few months the new cows were also producing milk with high levels of PFAS and Oakhurst severed their ties with Stone permanently.

“So the stuff is in my soil,” said Stone. “From there, it is in the groundwater that I give my cows, and in the grasses that I cut and feed my cows. It is in every part of them, milk, muscle, fat, and it doesn't go away. Ever.”

PFAS has contaminated virtually every American citizen, effecting the health of millions, and Stone and his family are no exception.

'My [health issue] is I have full blown Parkinson's;I fall down a lot and stuff and I take the meds for that. There's no [history of] Parkinson's in my family whatsoever. My wife has issues with different things. My blood level is 111 ppt.'

A visiting nurse helped Stone twice a week this past summer as he dealt with Edema affecting his legs, providing him with medication to cope with the pain, reduce the swelling and avoid infection of the open wounds.

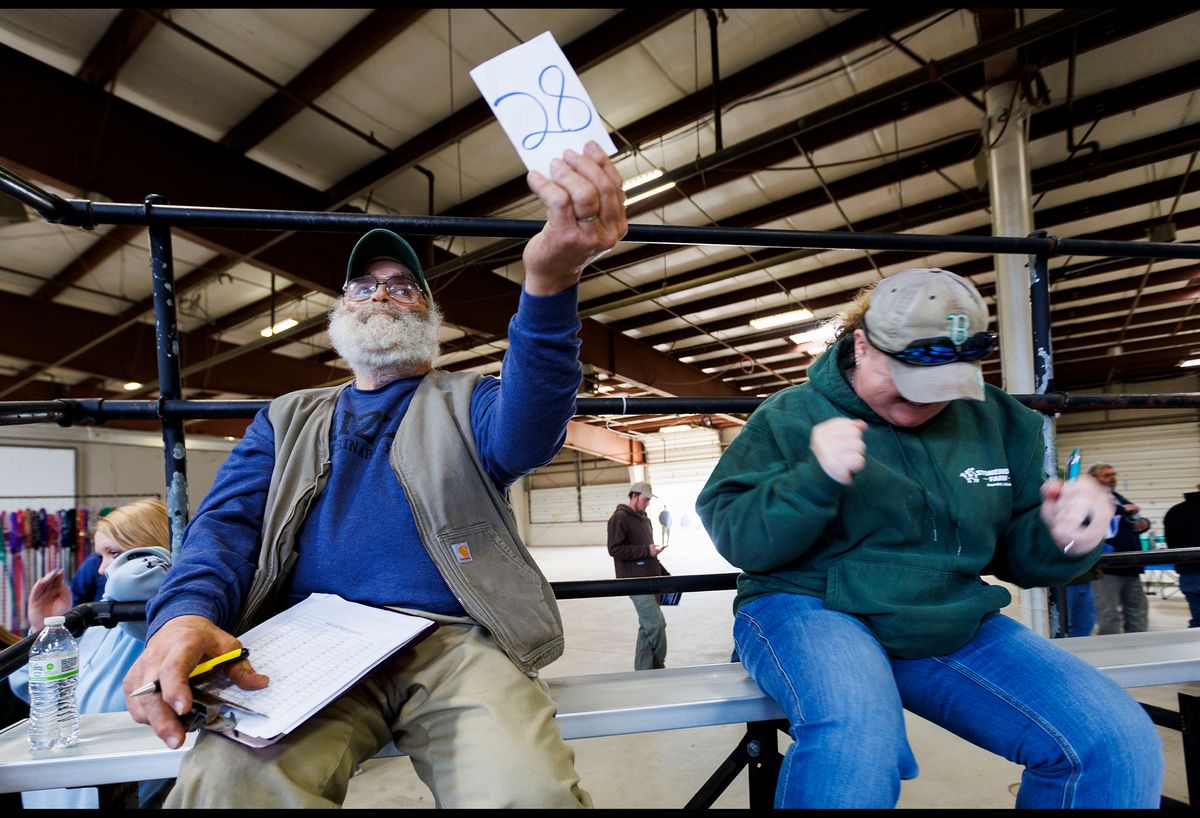

In 2023 Maine Congressman Wayne Perry got wind of the problems at Stone's and other state farms contaminated with PFAS. Perry introduced a bill that would require the State of Maine to reimburse farms and farmers damaged by the state-provided sludge that had contaminated their farms. But now over a year later, and several hearings, the money has not come and the bill is stalled in the legislature. Stone’s farm is bankrupt, but the reimbursement money could help save the farm and help pivot to a small direct dairy to creamery business.

Stone currently uses hay from Canada to feed his much smaller herd of cows, and has a large granular-activated carbon water filtration system, resulting in the PFAS levels in his cows coming down approximately 50% from when he was first notified of the contamination, but still the PFAS is detectable. And Stone has worrisome concerns about the feed he purchases for the cows. Despite his requests, the State has not done PFAS testing on the grain.

'They don't want to [test the feed] open that can of worms. Just like COVID, if you don't test [for it] then you don't know you have it - head in the sand approach. Not good.'

'I just want my milking license back and as long as I have cows and the farm, [The State of Maine] will have to put up with me running my loud mouth 'til something gets done.'